Are We Trading Safety for Surveillance?

Your aging parent falls in the kitchen while you're at work. Nobody hears them. Without the wearable alert, they lie there for hours. With the smartwatch, emergency services arrive in minutes. The technology saves their life. So when a provider suggests ambient sensors throughout their home motion detectors, activity monitors, fall detection you say yes. Of course you do. You want them safe.

But then you notice something. The care coordinator can see exactly when your parent uses the bathroom. The activity dashboard tracks their sleep patterns, their meal timing, their movement through the house throughout the day. You're monitoring not just that they're okay, but how they move, when they sleep, what they eat. The technology that was meant to catch emergencies has become a window into every moment of their private life.

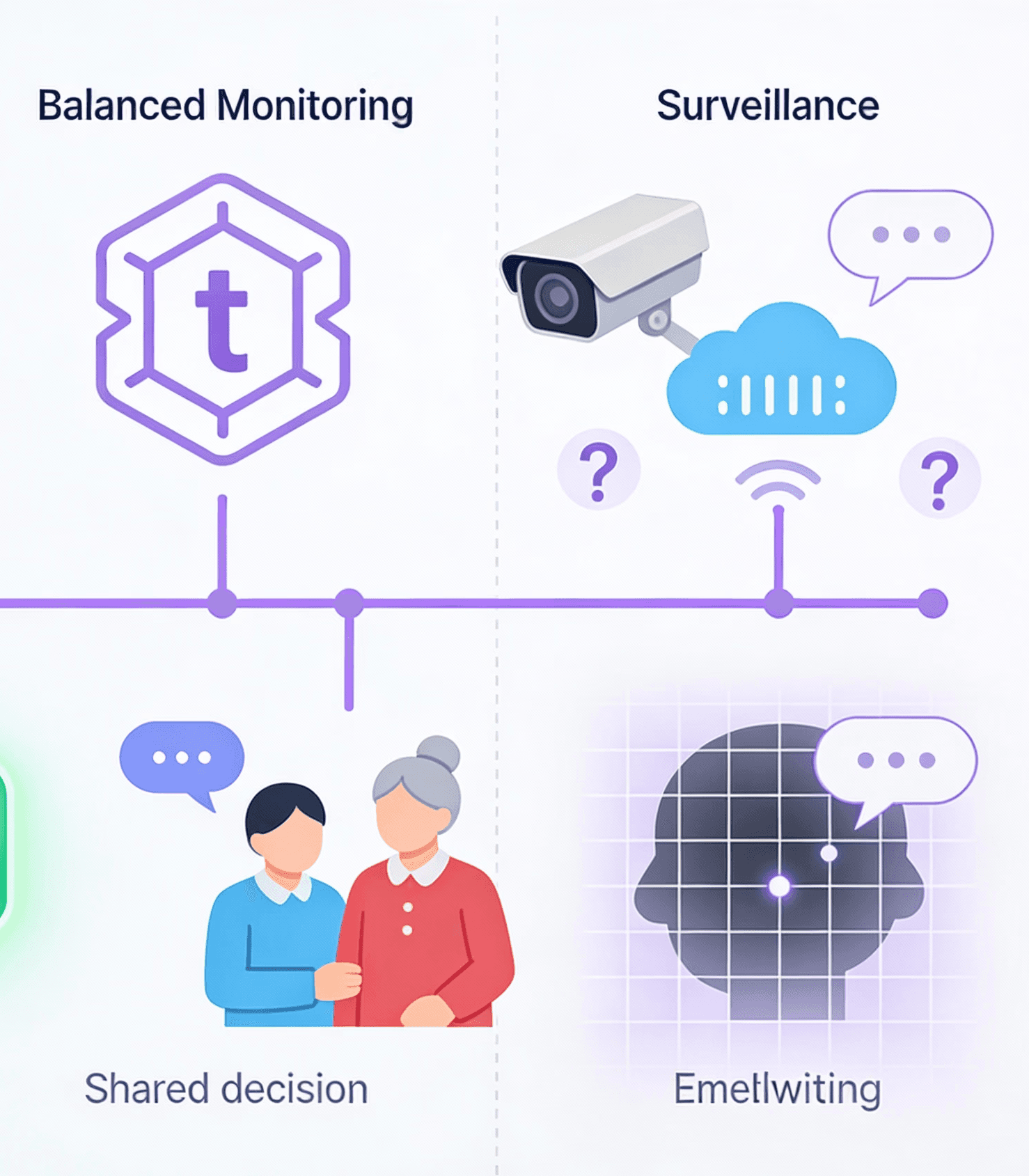

This isn't paranoia. This is the growing reality of elder care technology in 2026. Wearables and monitoring systems deliver genuine safety benefits fall detection, medication reminders, emergency alerts that work. The research is real. CSIRO trials showed a 10 times lower decline in quality of life for older people using sensor platforms versus standard care. Families report genuine peace of mind. But the technology industry has quietly crossed a line that ethicists, Dementia Australia, and aged care advocates are frantically trying to redraw: the line between monitoring for safety and surveillance for control.

The question isn't whether technology can help. It can. The question is: at what cost? And who gets to decide?

The Safety Promise We're Not Keeping

Start with what wearables actually deliver. Fall detection on smartwatches can alert caregivers and emergency services within minutes turning what might be a life-threatening injury into a managed incident. Medication reminders keep track of complex drug regimens. GPS devices help locate people with dementia who wander. Personal alarm buttons give immediate access to 24/7 nurse hotlines. In the real world, this technology prevents injuries, catches early health changes, and enables aging in place rather than premature institutional care.

The market is responding enthusiastically. Wearable fall alarm adoption in Australia is accelerating rapidly. Providers like INS LifeGuard offer 24/7 nurse monitoring. CSIRO's Smarter Safer Homes platform uses ambient sensors and AI to detect changes in behavioral patterns and the evidence of safety benefit is statistically significant. These aren't gimmicks. They're tools that work.

But here's what the safety narrative obscures: technology sold as "monitoring for safety" often becomes surveillance for control. The same ambient sensors that detect falls also track every bathroom visit, every time your parent gets out of bed, every moment of stillness that might indicate depression or health decline. The activity dashboard that shows "parent is active and engaging" also reveals "parent hasn't left the house in three days" or "parent's meal patterns have changed" useful clinical data, yes, but also an intimate window into solitude, routine, vulnerability.

Older adults themselves recognize this contradiction. In Australian World Cafés with 84 people aged 55+, participants expressed "cautious and conditional acceptance" of smart technologies, while identifying serious concerns about privacy, surveillance, and loss of autonomy. They want the safety benefits. They don't want to feel watched.

The gap between what technology claims to do and what it actually does to their sense of dignity is widening. Researchers at Oxford have documented that people under ambient sensor monitoring report feeling "being watched" even when nobody is actively reviewing the data. The constant potential for observation changes how people move through their own homes. It transforms private space into monitored space. Home becomes a care setting rather than a sanctuary.

The Consent Crisis Nobody's Talking About

Here's where the ethical line blurs almost beyond recognition: consent in the context of advanced age and cognitive decline.

Two-thirds of residents in residential aged care have moderate to severe cognitive impairment. This creates an almost impossible ethical situation. When a family is asked to consent to video surveillance of their parent with dementia, they're told it's for safety, for fall prevention, for documenting care quality. They sign the consent form. But what that form actually authorizes is continuous recording of a vulnerable person in their most private moments—bathing, toileting, dressing, medical procedures.

Here's the problem: People with dementia may forget they gave consent. They may later want to withdraw consent, but lack the cognitive capacity to do so. Enduring waivers signed at admission don't reflect changing wishes as the disease progresses. The person on camera may have had complete clarity when they signed, but six months later, as dementia advances, do they still understand they're being recorded? Can they meaningfully withdraw consent if they forget it exists?

Dementia Australia, the peak advocacy body, states plainly: "There is insufficient evidence to indicate whether video surveillance reduces serious incidents or improves care quality". And their position is even stronger on this point: "Dementia Australia does not endorse broad video surveillance usage in residential aged care settings". Why? Because the risks to dignity, autonomy, and privacy aren't offset by proven safety benefits. And because a South Australian trial suggested video surveillance may actually disrupt care delivery, resulting in negative impact on overall care quality.

The regulatory gap is stark. Australia has no national guidelines governing surveillance technology in aged care settings—despite the Aged Care Act 2024 mandating person-centered care with dignity and privacy at the center. Providers are deploying sensors with vague consent processes that don't account for cognitive decline, changing preferences, or the distinction between monitoring that something happened and continuous surveillance of how it happened.

Even the Australian Law Commission has warned: Surveillance technology may amount to a restrictive practice, with people with disabilities disproportionately subjected to monitoring in residential care settings. The very tool meant to protect vulnerable people can become a tool of control over them.

There's an unintended consequence that technology vendors don't discuss: the possibility that monitoring replaces human care rather than enhancing it. Healthcare professionals implementing remote monitoring in hospital-at-home settings reported that technology often created new work burdens rather than reducing them—formal carers already operating within tight time allocations suddenly had to manage device training, data interpretation, and new alert protocols, with no additional support.

More troubling: Over-reliance on remote monitoring and telehealth could actually result in older people spending more time alone, not less. The logic seems sound—technology watches them at home, so fewer in-person visits are needed. But isolation is a serious health risk. Social isolation in elderly populations has devastating consequences: depression, suicide risk, malnutrition, physical decline. A smartwatch might catch a fall. It doesn't catch the slow erosion of meaning that comes from solitude.

The alternative model—relational care enhanced by technology—looks different. Modest wearables (not blanket surveillance) give caregivers useful alerts. But the primary relationship remains human: a trusted neighbor, family member, or professional caregiver who visits regularly, who has context about your parent's life, who can interpret changes in behavior with understanding rather than algorithm. Technology supports that relationship. It doesn't replace it.

This is the core of CareNeighbour's philosophy: care is relational. It's built on trust between people who know each other, who are accountable to community, not to metrics. Technology can enhance that—but only if it remains secondary. When monitoring becomes the primary interface between your parent and their care system, something essential is lost.